I stopped trusting LinkedIn's ad recommendations

This will save you tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of dollars in wasted ad spend

I have a love/hate relationship with LinkedIn Ads.

I love it for being able to get in front of the exact people I want to reach.

I hate it for all of the “recommendations” they push that only guarantee a better bottom line for them, not me.

While at Refine Labs, I spent hours every day in the platform as it was a huge piece to the work we were doing with clients. When I moved over to Loxo, I started to become more removed from the day-to-day of it. This was a mistake.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve gotten my hands back into the weeds here and have unfortunately found we’ve been “relearning” some lessons. Interestingly, this topic has also come up recently with some peers at other organizations, so it seemed like this may be a good time to broaden that conversation out for all of you following along here as well.

So without further ado, here are the 5 biggest mistakes I’ve seen, learned, and relearned so that you can avoid them…

Sponsor: You/Your Company?

If you’re looking to get in front of an engaged audience of some of the savviest marketers + GTM practitioners, this is your opportunity. One opening per month to sponsor this newsletter has become available and I’m sure will claimed quick, so if the audience reading this newsletter is your ICP, this is your chance.

Just last week I was talking to a VP of Marketing and they said they were exploring and in negotiations with one of the sponsors of this newsletter after learning about them here + seeing them as a product that I endorse. That’s the power of these types of partnerships done well (vs. the AI influencer dumpster fire some are experimenting with).

Simply reply back to this email if you/your company is interested or drop me a DM on LinkedIn.

1) Segmentation is EVERYTHING

The number 1 mistake I see in LinkedIn Ads campaigns is the audience segmentation being an afterthought.

“We sell to recruiters, so our target audience is anyone who’s a recruiter or any organization that recruits for themselves.”

^^ Thank god we don’t operate that way here at Loxo with the market we serve (recruiters), but that’s an example of a conversation I had multiple times at Refine Labs with clients where I simply swapped out their “ICP” with ours. The above isn’t an ICP statement, it’s a Total Addressable Market (TAM) statement. ICP ≠ TAM.

“Should we start with a lookalike audience of our customer list?”

That’s a good thought + one route that many go. The logic is sound in theory, but it breaks down in practice.

Why? Because it’s giving all control to the platform to determine what a “lookalike” member is. The attributes that they’re matching off of. We assume the algorithms used by platforms are good at this.

Unfortunately, that’s not the case. Go run a campaign for a few days using a lookalike audience. Then go look at the demographics report to see who the ads have been served to. The companies of the members. Their job titles. Their locations.

Now you see why this isn’t a good idea.

“So where should we get started?”

If you’re reading this, in your gut you should have a strong sense for who your ICP is and who you should be targeting.

The industry(ies) you serve

The relevant job titles/functions who use your product

The countries you operate in

The company size(s) that get the most value (count of employees or company revenue)

Go build out this audience in LinkedIn Ads.

Then run a win/loss report from the past 12 months and drill into the details outlined above. Are you seeing the data reflect your gut? Depending on how near/far you are from this, calibrate your audience accordingly.

Pro tip: there’s no “magic number” that your audience size should be.

For some companies that only sell to Fortune 500 companies, your audience size might only be 10,000-20,000 people. That’s ok.

For some companies that sell into huge markets, your audience size might be 500,000-1,500,000 people. That’s ok.

Remember: LinkedIn will always “recommend” what guarantees a better bottom line for them, not us.

2) Campaign objectives are misunderstood

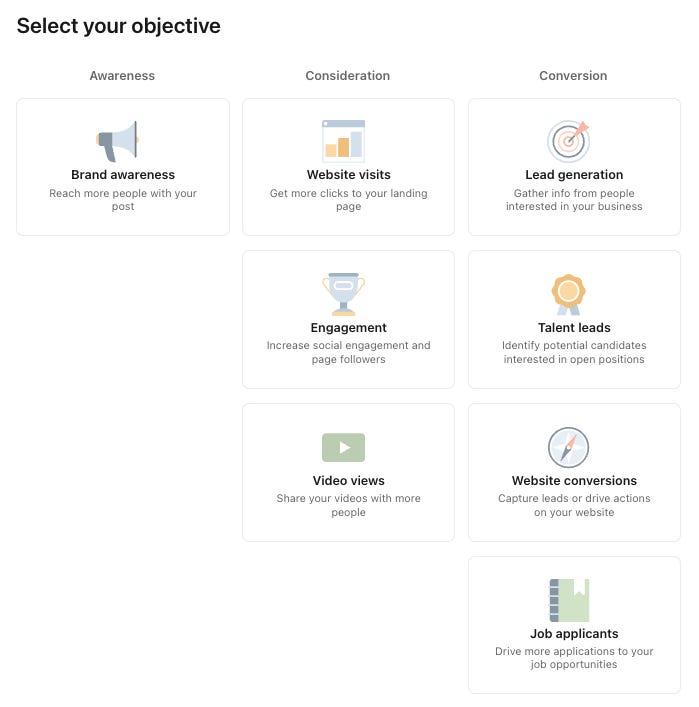

When creating a campaign, the very first thing that you’re prompted with is to select an “objective.”

Do you want to reach more people with your ads?

Get more clicks to your landing page?

Increase engagement?

Capture leads?

The answer you put in here determines the default “recommendations”.

It’s odd to think that they have you pick just one. In my head, I’m thinking, “D, all the above?” when making the decision.

So that should be the first thing that sets your spidey senses tingling.

Now, back to the very first thing we covered here - that segmentation is EVERYTHING. Let’s talk about why that’s so important in relation to this second point.

LinkedIn understands that most of their customers take the path of least resistance when building their audience. This is what makes the options here easier for them to “sell” you on.

“We’ll make sure your ads are served to those people most likely to click!”

”We’ll make sure your ads are put in front of those who will convert!”

”We’ll make sure your ads are shown to people who will watch your video!”

I’m not sure what mystical powers the individuals at LinkedIn have, but they must be pretty powerful if they can predict + control human behavior.

Today alone, I’ve watched a few videos in the feed from people I’ve never seen before because the content was interesting to me in how it stood out. I’ve also scrolled right past videos in the feed from people I’ve bingewatched videos from over the past few months.

Back to the point here - want to avoid letting LinkedIn make the “best” decision for you altogether? Have a defined audience list that you are confident in knowing that every single member is highly relevant and a prospective buyer, influencer, or user of your product/service.

Why? Because this allows us to bypass all of LinkedIn’s recommendations here and we can simply use the “Brand Awareness” objective. This objective is configured to show your ads to as many members of the audience as possible, at as efficient of a rate as possible. Or as Chris Walker would say in our early days at Refine Labs, “it’s guaranteed distribution to the exact people we want seeing the ads.”

No guessing human behavior.

No paying “more” because LinkedIn predicted they’d click.

No limiting your audience by assumptions.

Remember: LinkedIn will always “recommend” what guarantees a better bottom line for them, not us.

3) Do NOT let LinkedIn “optimize” anything

This is one I get heated about. It’s outsourcing your thinking + blindly following guidance without validating any proof behind the expertise.

Let’s go through two examples so I can show you what I mean + how this occurs:

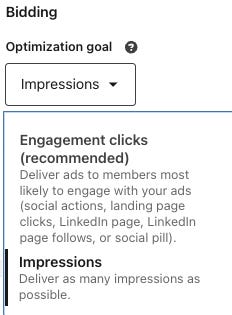

Bidding strategy

This section look familiar to you? For many, they scroll right past it as “Maximum delivery” is pre-selected and we assume this is the best route to take.

But what happens when you hit the toggle on it to see all of the options? That’s where your eyes should open.

In the instance above with an example audience I’ve built out, LinkedIn is “recommending” that I spend $115.12 for every 1000 impressions served. A CPM of $115.12 - are you mad!?

But then they try to soften it by showing what “similar advertisers” are bidding with an incredibly broad range, from $73 to $291 - a factor of 3.5x. Sound logic here…

This is telling you exactly what LinkedIn is going to charge you if you let them “optimize” this for you. Certainly no less than $115.12, but likely much more because “similar advertisers to you are also bidding here and we want to make sure you appear ahead of them.” Always so thoughtful to keep us in mind like that, that LinkedIn team.

Take back control here and use manual bidding. Give yourself a week to calibrate how low you can bid + still hit your daily budget.

Congrats, you’ve just found a way to take back 50-450% of your ad budget.

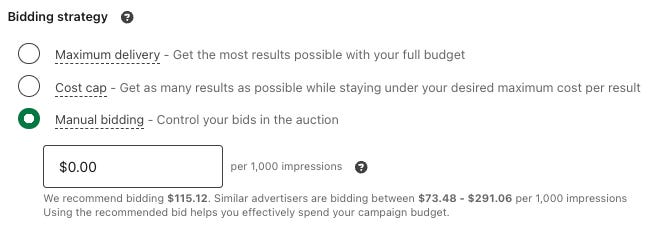

Ad rotation options

This one is buried in the ad creatives section of creating a campaign under the gear icon, so most don’t even know this exists.

It defaults to “Optimize for performance (recommended)”, stating that they’ll deliver evenly at first, then push more impressions to the creatives with the best performance.

“That sounds like sound logic to me, Sam. What’s the issue here?”

Well, how do you determine what “best performance” looks like?

Now go ask your colleagues that same question. And your manager. And your CMO. And your VP of Sales.

Bet you got a bunch of different answers.

So which one do you think LinkedIn aligns to? That’s a big black box.

We can only assume. Probably a factor of the objective you selected when creating the campaign. Either way, it’s likely not 100% aligned with your + your company’s definition of best performance.

And this is why we should be using the “Rotate ads evenly” option. It puts control back in your hands. You allow them all to run evenly in the beginning, and then YOU can look at the metrics that you know are leading indicators to what drives actual business results for your company to optimize your campaign from there.

Turning off low-performing ads

Increasing spend and impressions to high-performers

Iterating off of the high-performers to get even more in the mix

Remember: LinkedIn will always “recommend” what guarantees a better bottom line for them, not us.

(Are you starting to notice the trend yet as I keep ending each section with this? 😉)

4) Put safeguards in place

Beginning a few months ago, I noticed that there were some large prospect accounts in our campaigns that were getting a disproportionate amount of spend. I absolutely want to be showing up in front of them, but due to the size of their company and the number of potential users within them, well, let’s just say I could’ve easily covered my toddler’s grocery bill when it comes to her fruit consumption many times over.

So this tip actually comes from Canberk Beker who I go to for the LinkedIn Ads scenarios that stump me. And he never disappoints.

He said this is quite common. And even better, he has a way to help mitigate this from running rampant in our accounts.

Essentially, it’s looking at all of the accounts you’ve been serving ads to within a specific time window + mapping that to how much they are/aren’t engaging.

Here’s a company list template you might want to steal and use as an audience exclusion in your campaigns.

It’s effectively taking accounts over the last 30 days that are receiving a disproportionate amount of spend (impressions), but not engaging at a significant level compared to other prospective accounts.

Engagement here is a bucket that contains multiple behaviors + is why it works well. It looks across things like organic + paid ad impressions to engagement across paid and organic content (landing page clicks to “see more” clicks to reactions to share to video views, etc.).

Save this as a dynamic audience so that when an account drops below your impression threshold, they’ll come back into the campaign and resume seeing paid content.

Remember: LinkedIn will always “recommend” what guarantees a better bottom line for them, not us.

5) Use a metric that allows you to compare mediums correctly

The last + final one that I’ve talked about previously.

You have two campaigns running. You launched them at the same time and they’re targeting the same audience.

Here are the results you’ve seen so far:

Campaign 1:

→ 0.67% clickthrough rate (CTR)

→ $1.88 cost-per-click (CPC)

Campaign 2:

→ 3.50% clickthrough rate (CTR)

→ $0.33 cost-per-click (CPC)

QUICK - you just found out your budget was cut in half and you need to end one of these campaigns today. Which of these campaigns performed better and will be staying on?

You answered campaign 2, right?

Wrong.

These platform metrics do not take into account the MEDIUM that the content is being delivered in.

Campaign 1 was a video ad that played in-feed for the target audience. All they had to do was scroll through the feed as they normally would, and if they wanted to see the ad all they had to do was stop scrolling so they could watch it.

Campaign 2 was a static single-image ad shown in-feed for the target audience. All they had to do was read the text on the ad to get a sense of what it was about and then click on it to get to the content.

Here is the big kicker. The thing that needs to be taken into account here is that the goal is for the content to be CONSUMED.

For a video ad, you consume the content by watching the video in-feed.

For a static single-image ad, you consume the content by clicking on the ad to view the content that lives on a landing page.

Here are the keywords to hone in on: “watching” and “clicking”

If the goal of advertising is for the audience to consume the content you’re putting in front of them, here’s what that looks like for these mediums:

Static

Content lives on your website or somewhere that’s accessible “beyond the feed.” So the behavior here is:

See ad in feed > click > consume content off platform

Video

Content lives within the video and is accessible within the feed by playing it there. So the behavior here is:

See ad in feed > watch to consume content

A click isn’t required to consume the content in video, so CTR isn’t an apples-to-apples comparison.

An appropriate comparison is measuring the “cost per % of content consumed.”

For static, I use page scroll depth since a user has to scroll a page to read the content on your site. You can set this up in GA. I use 50%, 75% and 95% (no one scrolls to the bottom of the footer).

For video I use view percentages. Usually 50%, 75% and 100% (LinkedIn constrains you here).

As I mentioned earlier, I wrote an entire newsletter devoted to this one alone, so if you’re curious to go deeper, here’s where you can read more.

And remember: LinkedIn will always “recommend” what guarantees a better bottom line for them, not us.

Alright, that does it for this week. 5 tips to save you time, money, and sanity. And if you don’t see me in your feed next week, it’s likely because I’ve been blacklisted by LinkedIn for what I’ve shared above 😉😂

Book quote of the week

“Some fellows use language to conceal thought; but it’s been my experience that a good many more use it instead of thought. A business man’s conversation should be regulated by fewer and simpler rules than any other function of the human animal. They are:

Have something to say.

Say it.

Stop talking.Beginning before you know what you want to say and keeping on after you have said it lands a merchant in a lawsuit or the poorhouse.”

- Letters From A Self-Made Merchant to His Son, by George Lorimer

See you next Saturday,

Sam

P.S. if you liked today’s newsletter or have enjoyed some of the earlier ones, forward this along to a marketer you think would like it as well 🙂 This newsletter grows by word of mouth + I can see which weeks resonate more/less with you all based on how many people do (or don’t 😅) subscribe after reading.